Introduction

Photoshop is a program that has literally changed the world, or at least how we see it. In an era when virtually all imagery is digital, Photoshop sets the standard for creating and editing the ubiquitous digital images that we all encounter every day.

Photoshop is a huge program that would take “forever” to master completely. Furthermore, there are untold numbers of resources that can help you master the program’s features. So many, in fact, that it can be difficult to know where to start. This page simply introduces you to some basic techniques that can be used to prepare images for use with web pages.

We will start with some background material, and then move on to three basic Photoshop techniques that can be used in preparing images for the web. When you finish, you might decide that working with digital images is not for you, but you will at least have an idea of what the process is like. On the other hand, perhaps this will whet your appetite to learn more about working with digital images …

Background

You should already be familiar with Preparing Images For The Web, which introduces basic concepts about image file formats and how image files should be optimized for use on web pages. While Photoshop is usually thought of as a program for manipulating bit-mapped images, it also uses works with vector shapes in many situations. In particular, the third part of this page will deal with text manipulations that you will perform in Photoshop’s vector domain.

You can use Photoshop to create an image from scratch (“starting with a blank canvas” to use the painting analogy), or you can start with an existing image, typically a photograph, and change the properties of the image in various ways. Both techniques are used to produce images for the web. But before dealing with techniques, here is an example of how a photographer might use Photoshop to prepare a picture for printing. It’s not the same situation as preparing images for the web, but gives an idea of how Photoshop works.

Preparing a picture for printing

A photographer takes a picture with either a film or digital camera. If it’s film, the image has to be converted to a digital image using a scanner. Scanners and cameras typically produce JPEG image files, but higher-end digital cameras can produce images in a “camera raw” format (often written RAW for unknown reasons; it is not an acronym). If the image is a JPEG, it has had some color/exposure adjustments and compression applied to it by the camera or the scanner. Raw images have no compression or color adjustments applied to them, but they come in various file formats, depending on the camera manufacturer. Photoshop can work with JPEGs directly, but raw files have to be converted into a format that Photoshop can work with using a program called Adobe Camera Raw (ACR) that comes with Photoshop. ACR has a rich set of controls for making color and exposure adjustments before passing the image on to Photoshop. (ACR controls can do either less or much more extensive image adjustments than what is normally done in a digital camera or a scanner; the choice is up to you. A big advantage of working with raw images is that the ACR adjustments are non-destructive: they get added to the raw file as metadata rather than as changes to the pixel values recorded by the camera; they can be undone after the fact, if desired.

When a picture is opened by Photoshop, it is converted into an internal format that Photoshop can work with. If you edit the image, you can save your changes in any of several image file formats, including JPEG or PSD (“PhotoShop Document” format). If you start with a JPEG, you can save your changes either in the original file that you started with, or in a copy with a different file name. It is a lot smarter to keep the original file unchanged in case you do something in Photoshop that you later decide wasn’t such a good idea. If you want to preserve any layers you created in Photoshop, you have to save the file as a PSD. If you started with a raw file, you cannot save your edits back as a raw file, so you have to save it as a PSD file.

In Preparing Images For The Web, we talked about Photoshop’s “save for web and devices” option. When you use that option, (a) you are always saving a copy of your work that is separate from the JPEG or PSD file you started with; (b) there are other file formats you will pick from for your web copies in addition to JPEG, namely GIF, PNG-8, and PNG-24. (Actually, if you pick JPEG for the output from Save For Web & Devices, you could very easily overwrite the image you started with if it was a JPEG: be careful!)

Once the picture is open in Photoshop, you can manipulate it. In general, you have a choice of applying the manipulations on the image itself or on one or more “layers” that conceptually sit in front of the image layer. Once you change the image itself, there is much less flexibility for modifying those changes, so it is almost always wiser to create a new layer for each manipulation. Photoshop keeps the layers separate in a PSD file, which is why that format gives more options for re-editing an image than a JPEG does. If you save a file as a JPEG, all the layers first get “flattened” into a single layer.

Broadly speaking, there are four kinds of modifications a photo editor might do:

-

Change Geometry

This category refers to things like changing the intrinsic size of the image (cropping or enlarging), rotation, flipping, and warping. -

Adjustments

The basic adjustments mimic things that are normally done inside a digital camera or using ACR, but with a greater amount of control: Levels, Curves, Color Balance, and Brightness/Contrast. Other adjustments allow more “creative” adjustments, such as converting a color image to monochrome, or shifting colors in various ways. In addition there are a number of very powerful tools that can be used to retouch an image either for creative effects or to make it look “better” than the image the camera captured. The effects range from enhancement (similar to what a studio photographer might accomplish using sophisticated lighting) to creativity (like putting an elephant in a teacup) to outright fraud or deception. The boundaries are not always simple to state. (Is it all right to add someone to a group picture if they weren’t there when the picture was taken? Sometimes yes; sometimes no.) -

Filters

“Filters” are called that to evoke the optical filters that can be screwed onto the lens of a camera to affect the image that reaches the film (or sensor). Some traditional filters can change the color cast of a picture, others can distort an image in various ways. There are many patterns and textures that can be created using filters. An especially important set of filters for the digital photographer allow selective sharpening or blurring of parts of the image. (Sharpening cannot fix an out of focus image, but it can help make edges stand out better in a picture.) -

Layer Styles

Layer styles are effects that can be applied to shapes to give them drop shadows, contrasting edges, and various other effects that are best understood by experimentation. A photographer might put a white border around a photo, and add a drop style to the picture itself, for example:

Normally, a layer obscures the layers below it, but Photoshop also provides ways to mask out parts of a layer, blend layers together using over two dozen “blend modes”, and to control the opacity of layers.

Once the picture is ready for printing, the photographer would then use Photoshop to make sure the image’s color profile matches the ink/paper combination being used for printing, lay out the picture on the page, and send the image to the printer.

There are two important observations to make about the foregoing description:

- There are often many ways to accomplish a given effect. Sometimes this redundancy is provided so that users with different backgrounds will have familiar tools to work with. The dodge and burn tools and the photographic filters, for example, mimic the tools of the trade familiar to film photographers but not to someone who never used them in the past. Other times, a feature designed to do one thing can be pushed into doing something else by managing its settings in an unusual way. If you learn a technique for doing something, use it. But be open to discovering another way to do the same thing easier or better in the future.

- Layers are important. They are not intuitive to everyone, but you cannot avoid them entirely, and they add a great deal of flexibility to working with the program.

One more thing to recognize is that a lot of professionals work with Photoshop on a full-time basis, and there are lots of features in the program designed to make these people’s lives easier. There are ways to control how things are laid out on the screen, to setup keyboard shortcuts to reduce time spent with the mouse (or stylus; real pros use Wacom tablets), and to automate repetitive operations. One secret to learning Photoshop is to ignore the parts you don’t need.

Gradients

The first effect we are going to work on can be used to overcome some of the flat look that is the limit of what CSS can provide. Using gradients, colors and shapes can blend into each other, buttons can be made to look shiny, and parts of a page can be designed to create a sense of movement.

We will go over the process of creating the gradient image that is used for the background of this paragraph. Admittedly, this paragraph doesn’t look shiny or three dimensional, but it does show a gradation in color that can’t be achieved using CSS alone. To start, here is the CSS rule that was applied to this paragraph:

#gradient-paragraph { padding:1em; background:#ffc url(../images/lightRedGradient.png) top left repeat-y; }

The first thing to note is that the background color of the paragraph is different from the background of the rest of this section. You can click on these buttons to change that background color without changing the background image: (If you enable JavaScript for this page, you can experiment with changing the background color of the paragraph without changing the background image.)

The point of this demonstration is to show that the background image fades from a red color on the left to transparency on the right: if you change the background color, it shows through on the right side of the heading, but not on the left side. It also shows the concept of CSS box layers: the background color is behind the background image, which is behind the content. (If you do not specify a background color, it is transparent, and the background color of the element that contains the box shows through.) CSS box layers are not the same as Photoshop layers, but in both cases the effect is that a layer that is in front of other layers obscures the ones behind it. (Or in Photoshop terms, a layer above other layers obscures the ones below it.)

Other things to note about the CSS rule for the example are that the image is positioned at the top left of the heading (that is, the top left corner of the image is placed at the top left corner of the background box), and that the image repeats in the Y (vertical) direction. The CSS repeat-y value is often spoken of as “vertical tiling.”

Decide on the image’s intrinsic size

Before you start, you need to decide how large to make your background image. This is actually a complicated issue because you have to specify the intrinsic size of the image in pixels, but the size of the CSS box that you used it on depends on many factors: amount of text that goes in the box; font size and weight of the text; intrinsic sizes of any foreground images inside the box; padding and borders for the box; and explicit CSS settings for the width and height of the box. But really, since we are going to design an image that is tiled vertically as many times as necessary, it is only the horizontal size of the image that matters. But even that simplification yields no easy answers.

To add to the complexity, the width of the CSS box may also depend on the pixel dimensions of the viewer’s screen. Desktops and laptops have screen widths ranging from 768 to close to 2,000 pixels these days—but even with those numbers, there is no way to know how much of the screen a user will actually use for the browser window at a given time. At the other extreme, if your visitor is viewing the application on an iPhone, you know the browser will fill the 480×320 pixel screen—but you don’t know whether it will be held horizontally or vertically.

There are three basic ways to deal with this problem:

- Control the width of the containing box explicitly using the width, min-width, and/or max-width CSS properties.

- Use separate stylesheets for different categories of viewing devices. The style element has a media attribute that can be set to "screen" or "mobile". Using these attributes, you can have different style sheets for different viewing situations, with the the size of the background images adjusted for them.

- Take a best guess, and adjust the results. (I don’t think you would hear this in a graphic arts course.) This is the approach we will use: pick a width and see how it works. We can always go back and generate another image.

There is one last issue here: when tiling vertically, the image can be as little as one pixel high. This height would minimize the size of the image file, but there are two possible negatives: one is that the browser has to make more copies of a small image than a larger one in order to cover the background; the other is that it can be hard to see what you are doing on such a small image. We will make our image 20 pixels high so we can see what we are doing. Then we can reduce the file size by reducing the height as an optimization later if we want to.

Start Photoshop and get oriented

Start up Photoshop. In the lab, it’s Start—>Programs—>Adobe Web Premium CS3—>Adobe Photoshop CS3. The workspace will look different if you are using a different version from CS3, but what follows is pretty much independent of the version.

There is a vertical toolbar on the left, a set of panels and sub-panels on the right (also called “palettes”, a horizontal toolbar at the top, and a menu bar across the very top. An important item in the menu bar is the Window menu, which is used to select palettes to show if they are not currently visible. The horizontal toolbar at the top changes, depending on which tool you have selected from the vertical toolbar on the left.

The Photoshop user interface is intimidating because there are so many features and tools in the program. On top of that (actually, because of that), it is designed to be reorganized, rearranged, and customized to suit whatever task is at hand. Don’t worry about messing it up: Window—>Workspace brings up a set of options for resetting the workspace, palettes, and menus to their its default setups, so you can always get back to “normal” if things get out of hand.

Create a new image with a transparent background

Use File—>New to create a new image file. A panel comes up, and you could just click OK to accept all the default settings that show up: everything there can be changed while you are working on the image. But it is easier to set things up here.

- Change “Untitled-1” to a meaningful name for your image. We will use “600x20_red_gradient” for this exercise.

- Enter the image dimensions, in pixels. Besure to set the units to pixels.

- The Resolution does not matter because we already set the intrinsic dimensions of the image. But it is conventional to use a resolution of 72 to 90 for images destined for the web.

- Be sure the color mode is RGB Color, 8 bits per channel.

- Leave the Background Contents “White.” Our image will actually have a transparent background, but it is convenient to have a white background layer while working on it so we can see what we are doing better.

- Open up the Adavanced options and be sure the Color Profile is set to sRGB. Don’t worry about the other stuff in the color profile name; there is only one sRGB. The Pixel Aspect Ratio should be Square Pixels for web images.

A new window will come up showing your image. You can magnify or shrink it using Control_+ and Control_- to get it to a size you are comforatable working with.

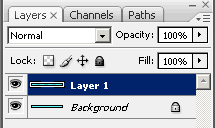

Create a new layer (Layer—>New—>Layer …. A panel will come up, the only setting you need to check is that the color is “None;” this will be the transparent background for the actual image. Find the Layers palette on the right side. It should now look like this:

The blue bar shows that Layer 1 (the one you just created) is “active.” Whatever you do now will affect that layer. The padlock on Layer 0 says it is locked and cannot be edited. The eyeball on the left of each layer shows that it is “visible.” You can click it to turn it on or off. Click on the Background eyeball to turn it off, and you will see that your image now has a gray and white checkerboard appearance, indicating that the only visible layer (Layer 1) is transparent and cannot be seen. (There may be a deep metaphysical truth involving visible layers that cannot be seen, but you will have to take that up someplace else—we have a gradient to build.)

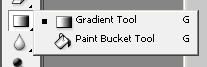

The gradient tool is in the middle of the vertical toolbar. It shares its position with the paint bucket tool, so if you see that instead, click and hold it for a few seconds and it will reveal the gradient tool option, which you can select. This screenshot shows the tool opened up to show both options. The ‘G’ is the keyboard shortcut you can use to select the tool; repeating it will toggle tools:

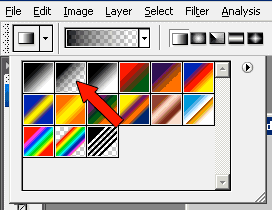

With the gradient tool selected, the horizontal toolbar at the top lets you configure the gradient(s) you are going to draw. The second tool in that bar has a downward–pointing arrow on the right that opens up set of predefined gradient types that you can select from. You want the second one, which goes from black to transparent, the one pointed to by the red arrow in this screenshot:

If you let your mouse hover over the place that the red arrow is pointing, you will get a tooltip that shows you the name of this gradient, “Foreground to transparent.” Before drawing the gradient, you need to set Photoshop’s foreground color. By default, Photoshop uses black and white as its foreground and background colors. These get changed all the time. (‘D’ changes them back to the default values of black and white; ‘X’ exchanges which is foregound and which is background.) One (of many) easy ways to set the foreground color is to click on the black square in the foreground/background tool towards the bottom of the vertical toolbar. This will bring up an elaborate color picker panel where you can select the new foreground color in many different ways. Use it to select a light red color (or other color of your liking), and you are ready to draw your gradient. Notice that the sample gradient in the horizontal toolbar changes to indicate the new foreground color.

Be sure Layer 1 is active, and drag a horizontal line across your image. You can hold the shift key to keep the line straight. Because the background layer is white, the image should go from red to white from left to right. Type Control_Shift_Z to undo your gradient, and draw another one from right to left. Undo that and draw one from top to bottom; at an angle; starting in the middle. Drag out the sides of window that holds the image so there is some gray space around the outside of it, and draw the gradient starting outside the image. Try drawing two gradients on the image at the same time. Try changing your foreground color and drawing another gradient. In a word: experiment.

Note that the gradient can have different shapes: experiment with radial and reflected gradients using the buttons to the right of the gradient type selector. Also, note that you can reverse the direction of the gradient and whether or not transparency works using the checkboxes further to the right of that. (To see how reflected works, start in the center of your image and drag towards either the left or right edge.)

This is strictly optional at this point, but you should know about it: If you double-click on the gradient type (second tool from the left on the horizontal toolbar), you will open up an elaborate panel for creating your own gradient style. In the middle of the panel is the control for setting up the gradient. On the top, there is a “stop” at both ends for controlling the opacity of the gradient at those ends; you can click on one to select it, and change the opacity at that end by entering a value in the lower part of the panel. You can also drag a stop to change its position, and you can create new stops simply by clicking anywhere along the top of the gradient where there is not a stop already. Then, to make things interesting, there is another pair of stops at the bottom for setting the color at various points along the length of the gradient. The preset gradients are shown at the top of the panel; clicking on one will show how the stops were set up to create it. In a word: play.

Back to work: Create linear gradient that starts with a red color on the left and fades to transparent on the right. End the gradient before getting to the right end of the image file; this will prevent a line break from appearing when the image does not cover the complete width of the CSS box for which it serves as a background.

Save your work. Since you have two layers, you should save the file as a PSD file to preserve all the information available.

Be sure Layer 1 is visible and the Background layer is invisible so your image is transparent on the right side. Use File—>Save Web & Devices to bring up the panel where you will optimize your image for use on the web. This is a big panel that lets you try out different file formats to see what gives you the effect you want in the smallest size possible. There are tabs at the top for “Original,” “Optimized,” “2-Up,” and “4-Up.” Select 4-Up, which will let you look at the original image you created and three alternatives.

By default, the three alternatives may or may not be useful. Photoshop will bring up the last file format you used in all three alternatives. But the first time you do this, you might get three different types of GIF files. GIG is unsuitable for this exercise because it allows only one level of transparency, and we need a gradual transition from opaque to transparent. (JPEG allows no transparency, so that format will not work either.) So select one of the alternatives (click on it and a blue border will appear around it), and change the drop-down menu on the right that says GIF to PNG-8. Click on another alternative, and change its format to PNG-24.

Feel free to experiment, but I think you will find that only the PNG-24 image format will give the smooth gradation to transparency that we are looking for. Both GIF and PNG use color look-up tables with just a single entry reserved for pure transparency. PNG-8 allows you to simulate degrees of transparency by “dithering” transparent pixels among solid color pixels, but GIF does not even offer this option, at least not in Photoshop.

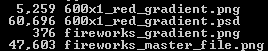

Truth in advertising: Photoshop is not the best tool for producing this image file. Fireworks, another program in Adobe’s “Creative Suite” (that’s what the “CS” in “CS3” stands for), was able to generate the equivalent gradient in a PNG file that was only 7% of the size of the one generated by Photoshop! Fireworks uses the PNG format as its native file format, so the following screenshot shows the sizes of the PSD file, the equivalent Fireworks PNG file, and the two PNG files optimized for the web. Not only is the Fireworks web image much smaller, but it the master file stores the gradient as vector data, which means you can go back to the original gradient and change its shape, position, stops, etc. Photoshop stores the gradient as a pixel matrix, so the only way to make changes is to erase the pixels and start over. But this is a Photoshop lesson, not a Fireworks lesson, so we will overlook this nasty little fact.

Save the PNG file in your web site’s images directory, add a CSS rule like the one shown previously to your web page. Be sure the name of the image file matches the file name in the CSS rule, of course. Congratulations! Now you can apply background gradients to any CSS box on your web pages.

Picture Tiles

There are two techniques that are often used to used pictures as backgrounds for elements like headings, where the element is likely to be much wider than it is tall. One is to use a big picture and present just a horizontal slice of it, and the other is to tile a picture horizontally. The latter technique is the focus of this section, but first, here is a digression on how to crop images, the technique used for the former technique.

Cropping (a digression)

Our cropping example is to start with this rather uninteresting snapshot …

… and to transform it into this striking design element:

Admittedly, real graphics designers would undoubtedly question whether this particular example represents a “striking design element”. (Or might cite it as a strking example of poor design.) But if you look around, you will see examples of this sort of thing on many web sites and in print. (Pictures of people’s eyes are popular.)

The above two examples were created as follows: First make a copy of the original picture file so you don’t accidentally destroy it using Photoshop. Now, instead of starting a new Photoshop document, use File—>Open to open the copy of the JPEG image. This one was a 10 megapixel file produced by the camera in the picture. Use Image—>Image Size… to bring up the panel for resizing images, and enter either the height or width of the image as you want it to appear on the web page, be sure the “Constrain Proportions” option is selected, and choose “Bicubic Sharper (best for reductions)” for the resampling algorithm. This reduces the image file size considerably, and prepares it for exporting using File—>Save Web & Devices. For photographs, the format for the web will probably be JPEG, and a low image quality (such as 30) will probably suffice. But you could experiment with PNG-24 to see if you could get a smaller image file. This process is for the first picture.

For the horizontal picture, open another copy of the original picture (so you have the full 10 megapixels to work with), and crop the image to the shape you want, and then resize it to the intrinsic resolution you want, and use File—>Save Web & Devices to export it for the web.

Like so many features of Photoshop, there is more than one way to crop an image. There is a crop tool on the vertical toolbar you can

use:  . But while the crop tool is the obvious choice for cropping an

image, it offers lots of options that can make it tricky to use. A simple technique for cutting out a piece of a picture (keeping the

pixels that you cut out unchanged) is to use the rectangular marquee toool,

. But while the crop tool is the obvious choice for cropping an

image, it offers lots of options that can make it tricky to use. A simple technique for cutting out a piece of a picture (keeping the

pixels that you cut out unchanged) is to use the rectangular marquee toool,  to make a selection of the part of the image you want, and then to use the

Image—>Crop menu item to make the crop.

to make a selection of the part of the image you want, and then to use the

Image—>Crop menu item to make the crop.

Making a picture tile-able

If you want to repeat a picture horizontally, you have to decide how to handle the seams between the copies of the picture. For example, you could transform this repeating image:

Into this:

The idea is to get the left and right edges to blend together, and the trick is first to put these two edges next to each other in the Photoshop window. To do this, make a copy of the picture you want to work with, open it, and use the Filter—>Other—>Offset… menu to bring up a panel that will let you offset the outside edges so they are in the middle of the image window. (You can also offset the top and bottom edges here if you were going to tile the image vertically.)

Fixing the image so there is no seam in the middle requires some practice with Photoshop’s retouching tools. The less the

difference to start with, the easier it is to do a passable job. One tool to work with is the patch tool:

. This tool shares a position with several others on the

vertical toolbar; if you don’t see it, the easiest way to find it is to type its keyboard shortcut, ‘J’, a

few times until it shows up. Be sure the options in the top toolbar are “Source” and not “Transparent.”

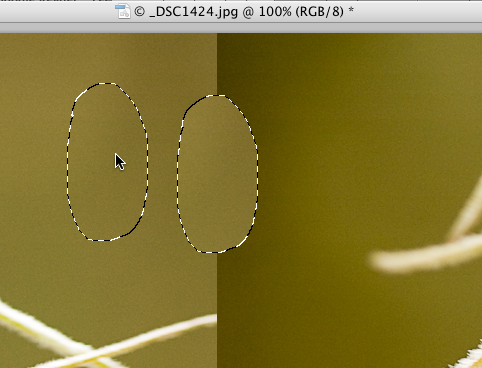

Virtually no image can be fixed in one step: you have to do it bit by bit. With the patch tool selected, drag out a shape

(“selection”) around a piece of the edge you want to fix. When you have surrounded it, let go of the mouse, and

you can then drag your selection to another part of the image; let go of the mouse, and Photoshop will blend the second piece of

the image over the first piece. Repeat this process until the center seam is not obvious.

. This tool shares a position with several others on the

vertical toolbar; if you don’t see it, the easiest way to find it is to type its keyboard shortcut, ‘J’, a

few times until it shows up. Be sure the options in the top toolbar are “Source” and not “Transparent.”

Virtually no image can be fixed in one step: you have to do it bit by bit. With the patch tool selected, drag out a shape

(“selection”) around a piece of the edge you want to fix. When you have surrounded it, let go of the mouse, and

you can then drag your selection to another part of the image; let go of the mouse, and Photoshop will blend the second piece of

the image over the first piece. Repeat this process until the center seam is not obvious.

The screenshot below shows the process at the point when a piece of the seam has been selected and dragged to the left. When you try it, you will see that the edges of the patched area will be blended with the area surrounding the patch; you may need to patch the edges of the patch to get a smooth blend all around.

Text Headings

People care a lot about fonts, the shapes of the letters that we see in print and on the screen. A font file tells how to render (draw) images of characters, and you have to have a font file installed in your computer in order to use that font. We aquire font files in a number of ways: some come with the operating system (but Windows, Macintosh, and Linux generally come with different sets of font files); some come with application programs, like Microsoft Office or Adobe Photoshop; others are available for free on the internet; still others are available only for people who pay for them. It would be nice if we could pick the fonts to use on our web pages and count on all our viewers to be able to see our web pages as we designed them. But to do that would mean supplying each viewer with a copy of each font file used by our web pages which is neither practical or, often, even legal at the present time.

In this section we will see how to use any font that is available on your own computer to generate an image file containing text that you can display on a web page using an img element. The problems with this approach are that users may have images disabled and that the use of image files for textual content makes updating either the content or appearance of the text an elaborate process involving another trip through Photoshop.

For this exercise, open Photoshop and create a new image file. Make the size of the image larger than you think you will need to hold the text; you can trim it to size later. The text you add to the file will go on a layer with a transparent background, so start with a white background layer that will let you see what you are doing.

Once you select the text tool from the vertical toolbar (the tool with a T for an icon), you can simply click in the image and start typing. There are four different type tools, so be sure you have selected the Horizontal Type Tool. The horizontal options bar at the top will let you select your text’s properties before you type, or you can type in your text, then select it and change the properties afterwards.

Each text layer keeps the text information as vectors, which means that you can change the text properties (font, weight, color, size, alignment) and even the contents without worrying about pixelation. For example, if you create some type using a size of 52 points, you can double the height and width of the image, and the text will automatically scale up to 104 points while retaining crisp edges. You can’t do that with bitmapped images, like photographs. But once you “rasterize” a text layer, you can no longer edit it. (Photoshop will warn you if you try to do something that requires rasterizing a text layer.)

Once you have created your text, you can turn off the background layer and save the image as a PNG file with transparency so that the background of the element shows through:

Note that it is critical that you set the alt text of the img file to be the same as the text in the image. Otherwise, someone with images disabled or otherwise invisible would not know what the text says.

Finally, you can use Phototshop’s “Layer styles” to add interesting effects to the text, such as an outline, a drop shadow, or an inner “glow”, all of which are configurable in a number of ways. (Experiment/Play!). To add layer styles to a text layer, select it and then click on the "fx" icon at the bottom of the layer panel. Here is the above text and background after adding a drop shadow, a 2 pixel orange “stroke” (outline), and a 4 pixel red inner glow to the text:

Note that if you edit the text (change the words or font or font size, etc.), the layer style will apply to the new text; it is attached to the outlines of the letters, not a bit-mapped part of the image.